The Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason roughly spans from the 17th to the 18th century. It stretched all across Europe and in the New World of North America.

It wasn’t merely a historical period, but a revolution of thinking. It was a transitional period from the old, unquestioned rules and traditions to a more rational world. One that wasn’t based on superstitions but reason, individuality, and freedom.

This period gave birth to some of the most genius minds of our world. And the ideas that they sparked still live on in the many discoveries of our world. Let’s find out what started the Age of Enlightenment.

The Age of Enlightenment or the Age of Reason roughly spans from the 17th to the 18th century. It stretched all across Europe and in the New World of North America.

It wasn’t merely a historical period, but a revolution of thinking. It was a transitional period from the old, unquestioned rules and traditions to a more rational world. One that wasn’t based on superstitions but reason, individuality, and freedom.

This period gave birth to some of the most genius minds of our world. And the ideas that they sparked still live on in the many discoveries of our world. Let’s find out what started the Age of Enlightenment.

In this article

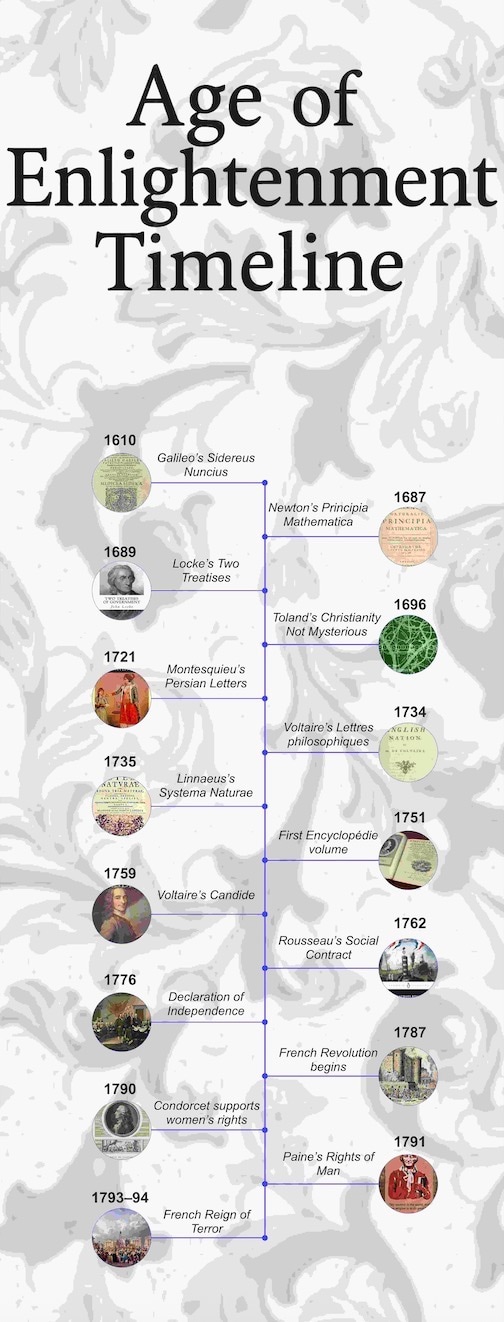

Age of Enlightenment Timeline

1610

In 1610, Galileo Galilei released Sidereus Nuncius. It was a book that shook everyone’s beliefs about the universe. Through his telescope, he spotted four moons orbiting Jupiter. It was direct proof that not everything circled the Earth. This directly challenged the long-trusted Ptolemaic model. It was a big “told you so” moment for Copernicus’s heliocentric theory as well. It was thrilling, controversial, and a little dangerous.

Back then, publishing a star chart could get you into more trouble than politics. And it did. For his support of heliocentrism, Galileo spent the rest of his life under house arrest. And remained there until he died in 1642 – poor guy.

1687

In 1687, Isaac Newton released his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. A title as heavy as the ideas inside. He revealed his three laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation. Linking falling apples to orbiting planets. He showed that the same forces moving the planets also shaped life on Earth. His work tied the heavens and the Earth together under one set of rules.

At a time when Europe was just starting to embrace reason, Newton’s book proved that nature wasn’t chaos. But a grand design running like clockwork.

1689

In 1689, John Locke wrapped up his Two Treatises of Government. It was groundbreaking. Locke argued that people are born with natural rights. Life, liberty, and property. And that rulers only get to keep power if they serve the public good. No divine right, no unquestionable authority. Just a deal between the governed and those who govern.

His ideas became the backbone of political liberalism. And, years later, it would echo loudly in the American and French revolutions. Not bad for a philosopher, I’d say.

1696

In 1696, John Toland stirred the pot with Christianity Not Mysterious. He was a devoted Deist. He claimed the Gospels held nothing that went against reason. And nothing that sat above it, either. He argued, if a doctrine truly rose “above reason,” it might as well be gibberish to human minds.

They were bold words. Especially in a time when questioning religious tradition could earn you more enemies than friends (remember what happened to Galileo?). Still, Toland’s work pushed the Enlightenment ideal that faith and reason didn’t have to be sworn enemies.

1721

Now, in 1721, Montesquieu made his literary debut with Lettres persanes (Persian Letters). Disguised as the observations of two Persian travelers in France, the book was actually a mockery.

It slyly poked fun at Parisian life. Mocked every social class. And took swipes at the freshly ended reign of Louis XIV. It even toyed with Thomas Hobbes’s ideas about the state of nature. And slipped in sharp satire about the absurdity of the Roman Catholic doctrine.

His work perfectly captures the Enlightenment’s growing appetite for questioning everything. What an interesting time to live in.

1734

In 1734, Voltaire lit a match with his Lettres philosophiques. In its pages, he aimed at France’s religious and political systems. Praising English freedoms while criticizing his own country’s rigid ways.

The reaction? Pure outrage. Authorities condemned the book. Ordered it burned. And made it clear Voltaire wasn’t welcome in Paris. He fled, of course – though not quietly. The scandal only boosted his reputation. His work may not have directly caused the French Revolution, but it definitely laid the groundwork for it.

1735

In 1735, Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus wrote the Systema Naturae. In which he divided the natural world into three kingdoms. Stones, plants, and animals. Then broke them down into classes, orders, genera, species, and varieties. For the first time, life (and even rocks) had a tidy filing system. Though science has updated his work, the structure he created is still the backbone of biology today.

1751

In 1751, the first volume of the Encyclopédie rolled off the press in France. Led by the philosophes, it aimed to gather all human knowledge in one place. It celebrated reason, science, and the belief that progress was possible. Over the years, it grew into 35 volumes. Becoming a monument to Enlightenment optimism.

1759

In 1759, Voltaire struck again in his new work, Candide. A razor-sharp satirical novel that mocked blind optimism, corrupt leaders, and the idea that “all is for the best.” Packed with wit, absurd adventures, and dark humor, it was more than entertainment. It was a critique of the world’s injustices, dressed up as a story.

Candide became one of the Enlightenment’s most enduring works. Voltaire’s work always managed to make people think. Especially about the topics they deemed uncomfortable.

1762

In 1762, Jean-Jacques Rousseau shook political thought with Du Contrat social (The Social Contract). He challenged the long-accepted idea that laws gained authority. Either from the rulers or the church. Instead, Rousseau argued that laws were legitimate only when they reflected the “general will” of the people. He claimed, power belonged collectively. Not handed down from above. His vision of a society built on shared agreement inspired future revolutions. And safe to say – made monarchs everywhere a little uneasy.

1776

In 1776, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia approved the Declaration of Independence. Written mostly by Thomas Jefferson, it declared the 13 American colonies free from British rule. It called for government by consent, unalienable rights, and the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness. It was a manifesto redefining American freedom.

1787

By 1787, France’s monarchy was running out of money. And its people were out of patience. When the regime tried to raise taxes on the privileged classes, it triggered a political crisis. Years of inequality, debt, and Enlightenment ideas boiling in the public mind came to a head. This unrest marked the first rumblings of the French Revolution. A movement that would upend the old order and attempt to rebuild society.

1790

In 1790, the marquis de Condorcet published On the Admission of Women to the Rights of Citizenship. His argument was simple but revolutionary. If men’s natural rights were based on reason and moral capacity, women deserved those same rights. Few male thinkers of the Enlightenment went this far. Making Condorcet one of the rare voices openly advocating full legal and social equality for women. His words planted seeds that are… unfortunately, still under development.

1791

In 1791, Thomas Paine released The Rights of Man. A fiery defense of the French Revolution and a call for republican government. He argued that political power came from the people, not kings. And that society should protect the rights of all its members. It was read across Europe and the Americas. Paine’s work became a rallying cry for all people facing injustice.

1793–1794

During the French Revolution, or the Reign of Terror. Leaders were gripped by suspicion. They targeted anyone seen as an enemy of the revolution. In Paris, the guillotine worked relentlessly. While in the provinces, local committees and “representatives on mission” punished in any way they saw fit.

Around 300,000 people were arrested. 17,000 officially executed. And thousands more died in prison or without trial. It was a chilling time. And a reminder that revolutions aren’t easy.

How to Make a Similar Timeline in EdrawMax?

The Age of Enlightenment is one of the most influential intellectual movements in history. Reshaping politics, science, and society between the 17th and 18th centuries. A timeline is a great way to follow its key moments from start to finish.

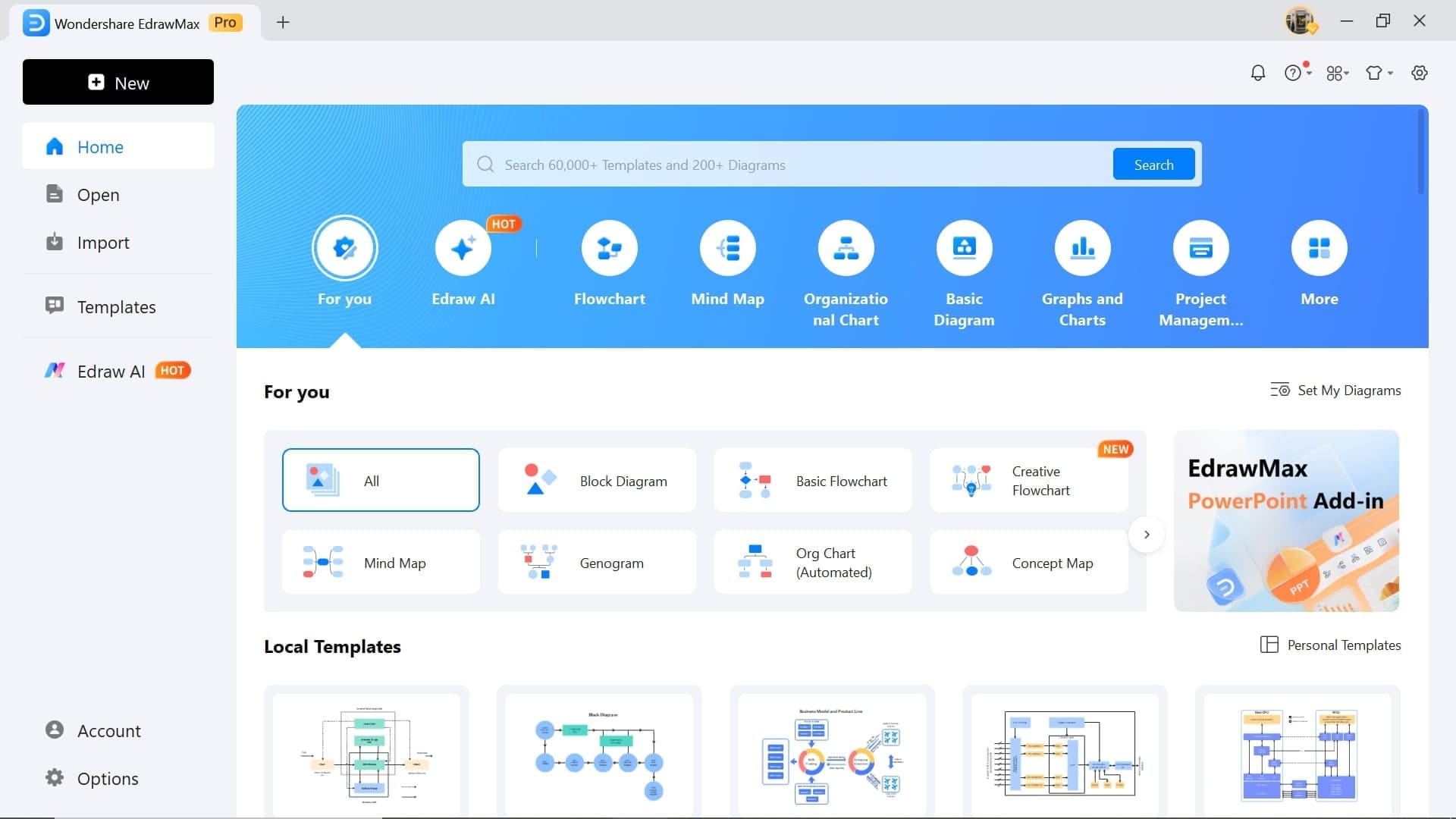

If you’re just starting with timeline creation, EdrawMax, a perfect timeline software, makes the process simple. It’s designed with beginners in mind. Giving you all the tools you need to bring the Enlightenment’s story to life.

Let’s get started:

Step1Install EdrawMax

- Download and install EdrawMax.

- Sign up or log in to begin.

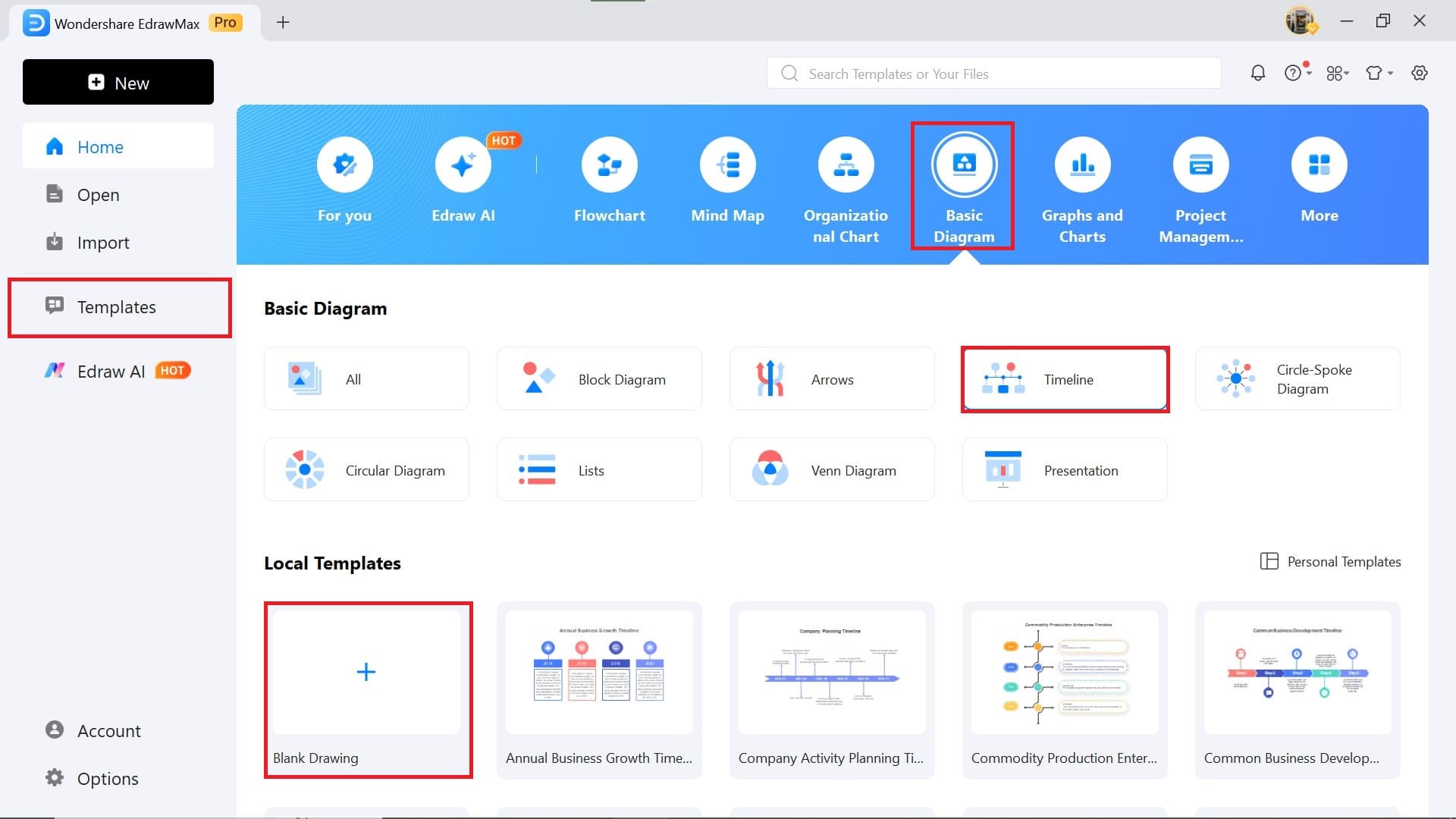

Step2Create a Timeline

- From the homepage, go to Basic Diagram > Timeline > Blank Drawing.

- Start from scratch.

- Or pick a pre-made template from the Templates library.

- Let’s start from scratch for this tutorial by choosing Blank Drawing.

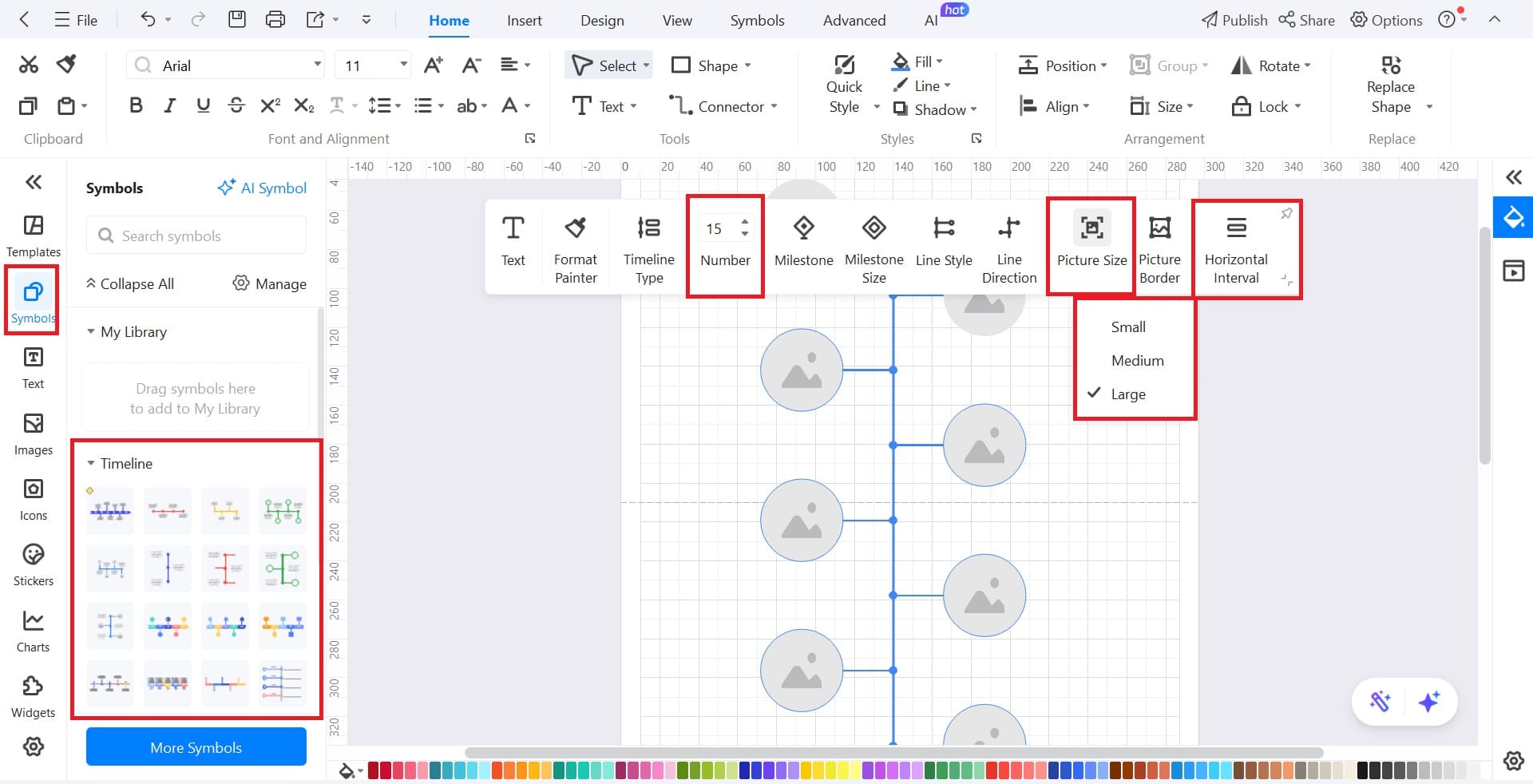

Step3Build the Timeline

- In the Symbols panel, choose a timeline layout and drag it onto the canvas.

- Click the timeline to open editing options.

- Adjust connectors, picture size, and horizontal spacing for each layout.

- Start by heading to Numbers, Picture Size, and Horizontal Interval, respectively.

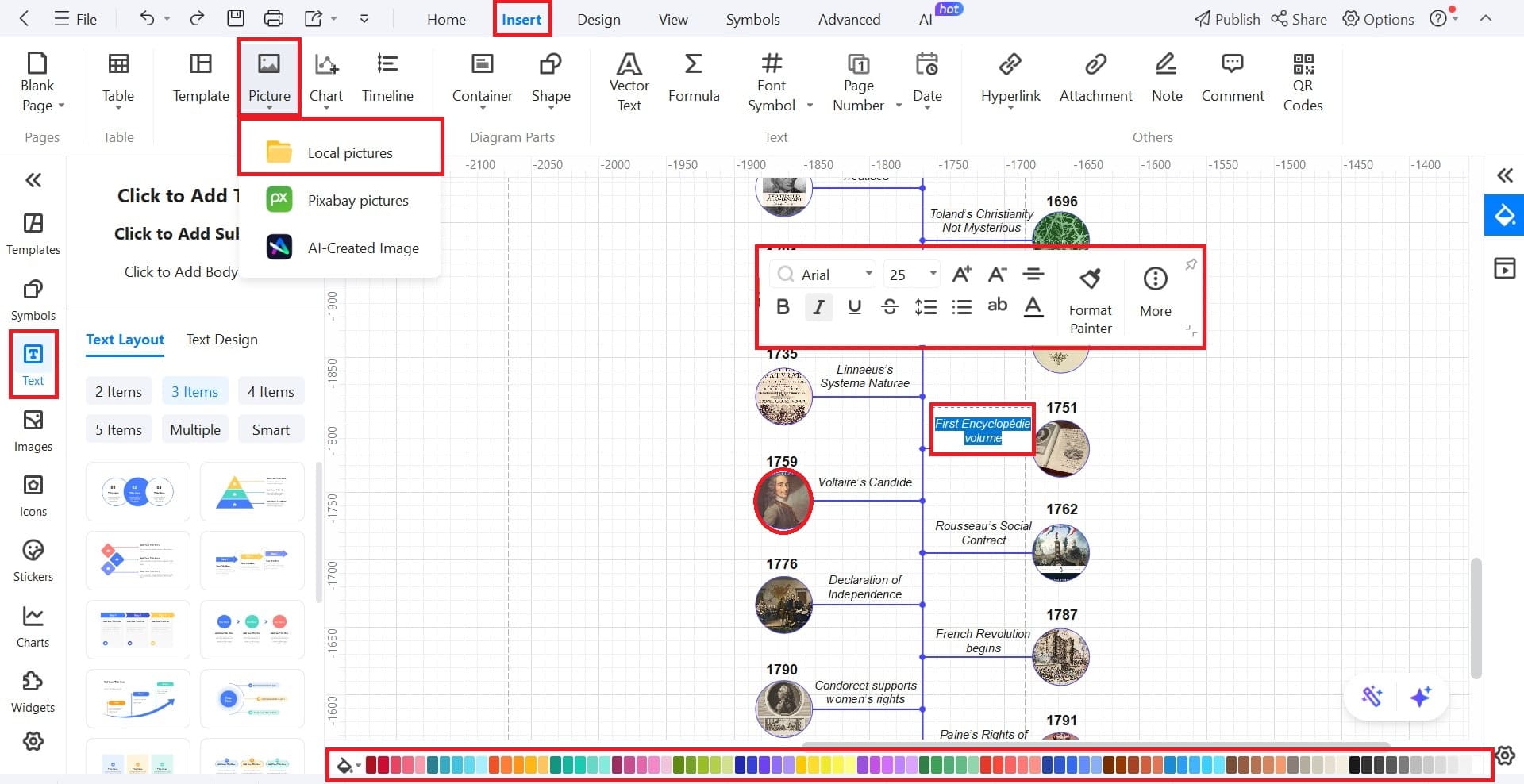

Step4Personalize the Timeline

- Double-click to add text.

- You can also drag-and-drop a text box from the Text section.

- Change timeline color using the quick color bar.

- Insert images via Insert > Picture > Local Pictures and drag them into frames.

- Pictures fit automatically. No need to resize each one.

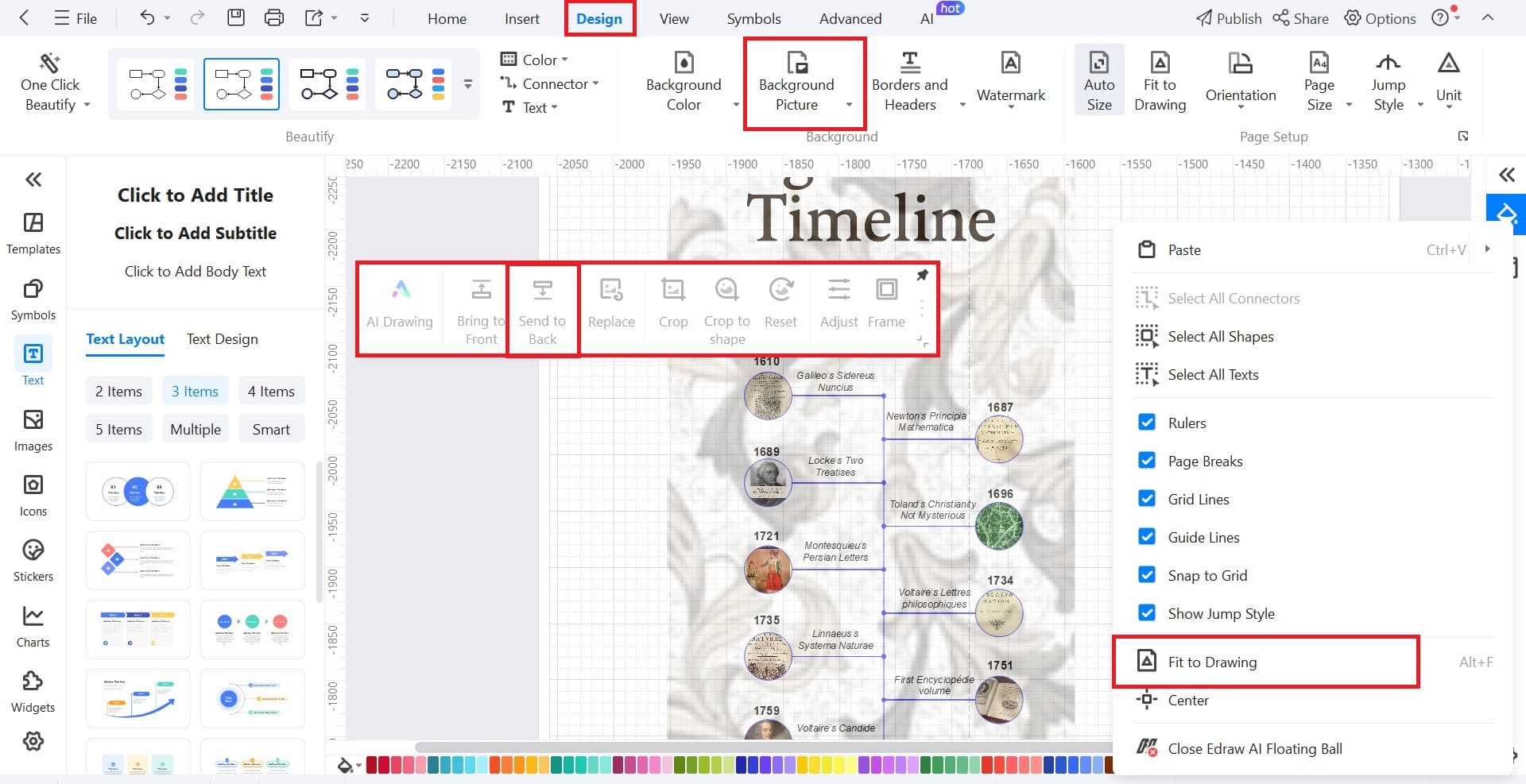

Step5Design the Background

- For a background, use the Design bar > Background Picture.

- Or upload your own from your device.

- If you choose the latter method, click the image, then Send to Back.

- For the final touches, right-click the white canvas.

- Select Fit to Drawing.

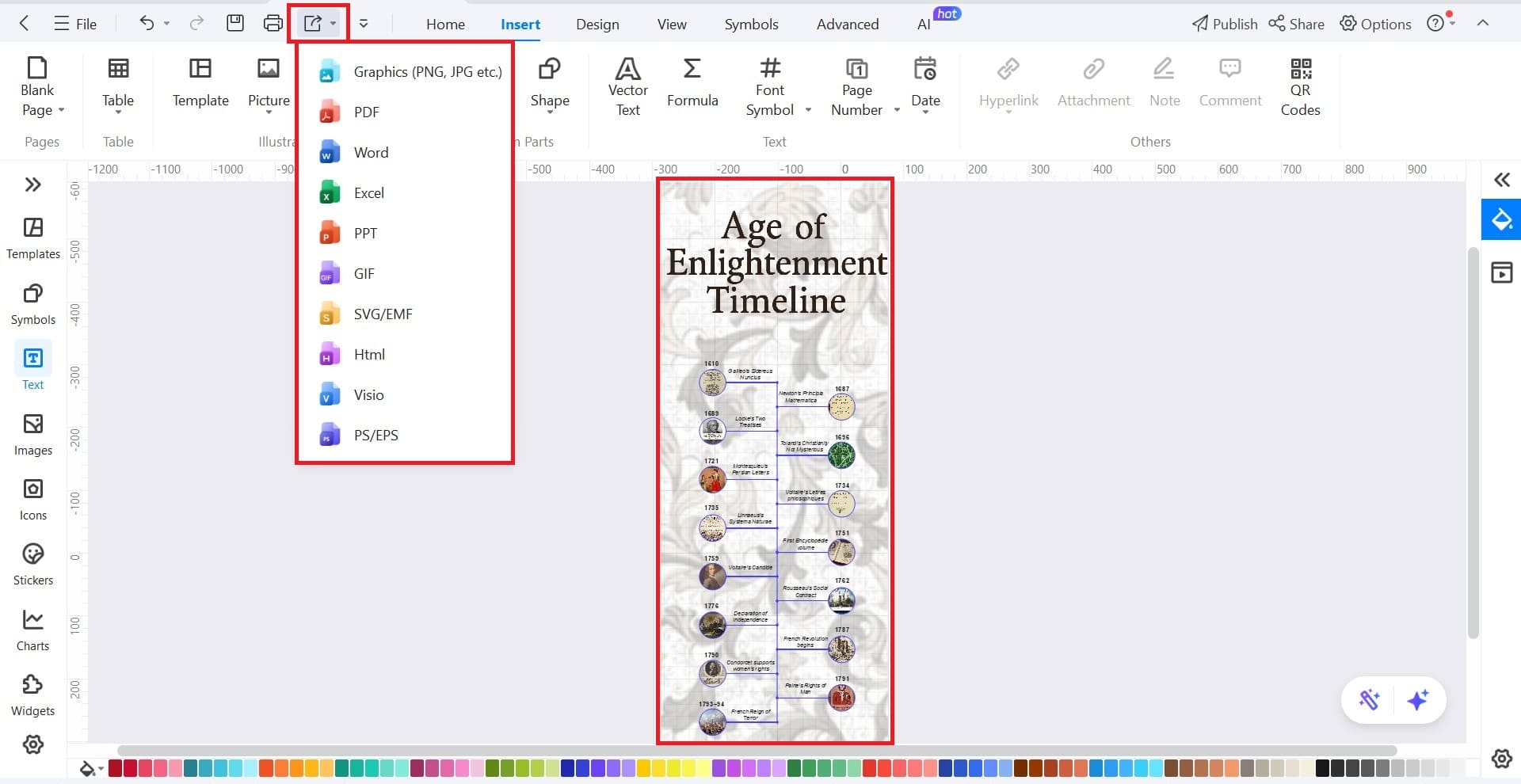

Step6Export the Timeline

- Click the Export icon.

- Choose one of the formats from the drop-down menu.

- Save your file.

- That’s how you make a timeline in EdrawMax. Simple and efficient.

Ending Notes

Now you know everything about the Age of Reason. And suffice it to say that it does live up to its name quite well. Who knows what would’ve happened to our world without this time? If mankind hadn’t gotten itself free from the shackles of superstition. And started to ponder.

If you also want to broaden your horizons and skills. Try using EdrawMax. It’ll not only help with your timelines but also expand your learning capacity.